Ramen and Miso Madness

When Americans discovered sushi, the flood gates to Japanese cuisine opened wide. Years later, we’re still hooked on sushi but we’re even more happily awash in miso and ramen, which may soon be the most popular Japanese dish in the United States.

Miso soup is so entrenched that we barely give it a thought.

“Miso, the standard Japanese breakfast or side dish, actually originated in China in the 4th century B.C.,” says Chef Kimmy Tang of 9021Pho.

“Buddhist monks brought this nutritious paste of fermented rice, barley and soybeans to Japan about 750 A.D. Cooks mixed it with dashi stock to make the healthy dish that became a samurai staple.”

By the Kamakura period (1192–1333), miso soups served with rice and pickled vegetables had become common.

People tweaked their recipes with seasonal ingredients. They contrasted forceful additions with delicate ones and balanced seaweed and other foods that float with those that sink like potatoes. Different regions developed their own varieties: shiromiso in Kyoto, hatchomiso in Aichi Prefecture and shinshu in Nagano. On Awashima Island off the coast of Nigata, cooks prepare wappani miso soup without fire by filling a cedar flask known as a wappa with broth, fish and vegetables with heat-retaining hot rocks. In the Edo period (1603 to 1868) Hikone beef preserved in miso was a treasured gift for the shogun of Tokyo. Christian Japanese refugees who came to the Philippines at this time added tamarind’s sweet-and-sour flavor to their miso soup.

Saveur Magazine lists more than 20 miso dishes that include sauces, glazes, marinades, dressings and Japanese-Style Chicken Curry… as well as some unexpected ingredients such as chocolate and milk. The website seriouseats.com has many more recipes but because miso is so time consuming and labor intensive, it is usually only restaurant chefs who make it from scratch.

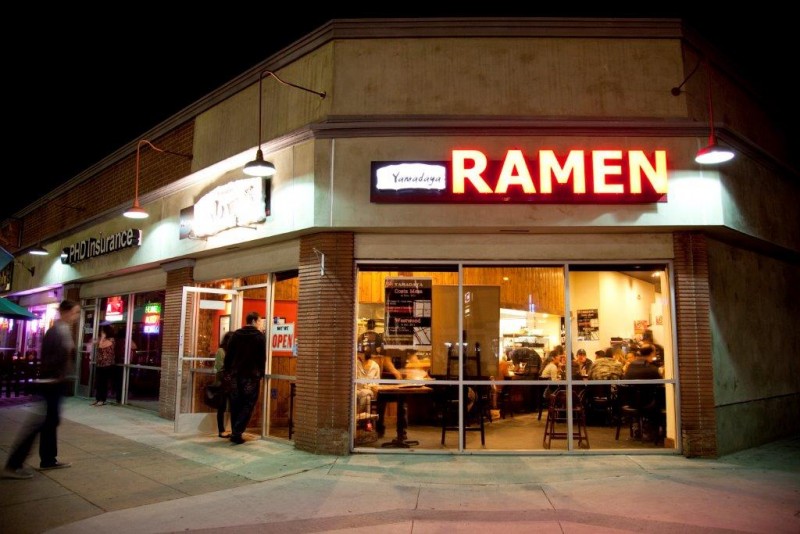

Sapporo and Hokkaido chefs steep their noodles in miso-based broth to make ramen. Sapporo is also the home of Sapporo beer and Sapporo Ichiban is now producing a line of instant noodles in a microwave-safe bowl with the unlikely image of Ivan Orkin. When the New Yorker saw Juzo Itami’s 1986 satiric comedy Tampopo about two truck drivers who help turn a decrepit roadside ramen shop into a noodle oasis, he found his life’s mission. Undaunted by the 80,000 ramen shops already in Tokyo, he went to cooking school and then moved to Japan where he devoted himself to the noodle dish. He opened the wildly successful Ivan Ramen in 2007 before bringing his concept to New York City.

Ramen also has roots in China, where it is sometimes called chukka soba (“Chinese noodles”). Although every Japanese city has numerous inexpensive ramen restaurants specializing in these noodles, the four main types are shio (“salt”), shoyu (“soy sauce”), tonkotsu (“pork bone”) and miso (“soybean paste”).

Fukuoka is famous for originating the Hakata style of ramen. The region’s tonkotsu broth is rich, milky and pungent. It’s traditionally paired with thin, straight noodles and is often served with crushed garlic and sesame seeds. Westerners are avid adherents of tonkotsu but many Asians find it too rich. However, it’s the style that is sweeping America.

Ramen is so popular that Japan is looking for “Ramen Ambassadors” or non-Japanese expats who love ramen and want to blog about their obsession to the world. It’s unlikely that any of them will compare with Rickmond Wong the Rameniac (rameniac.com) who is an expert on all things ramen. He visits Japan frequently, appears to live on ramen and explains the regional styles of ramen on his blog while offering reviews of both restaurants and packaged products. Food critic Jonathan Gold says when Tsujita opened in Little Osaka on Sawtelle Avenue in Los Angeles, “it was filled with L.A.’s noodlerati” and since Rameniac was stuck in London, he “was observing his friends eat noodles” on skype.

At the ultra-exclusive Fujimaki Gekijyo restaurant in Tokyo, Five-Taste Blend Imperial Noodles are made with more than twenty ingredients, including high quality Chinese stock as well as a spicier stock inspired by Thai tom yum soup. A bowl of Fujimaki ramen costs $110.

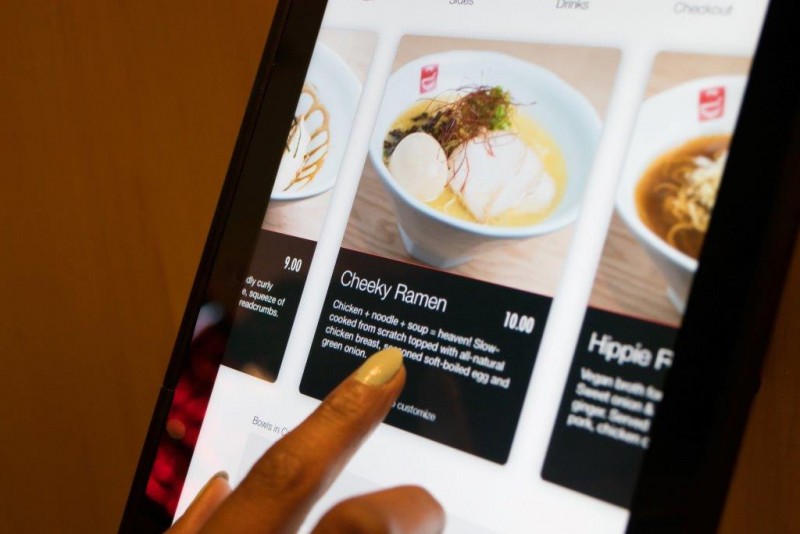

On a more attainable level, Momofuku Ando saved home cooks with his invention of packaged ramen which is now as popular in Europe and America as in Japan. His life inspired Andy Raskin’s memoir The Ramen King and I: How the Inventor of Instant Noodles Fixed My Love Life. Three museums in Japan salute the staple that became a phenomenon. Shin-Yokohama Ramen Museum evokes 1950s Tokyo… the Nissan food company opened the Instant Ramen Museum in Osaka, the birthplace of Cup Noodles… and the Cup Noodles Museum in Yokohama offers a fever dream of 3,000 kinds of cup noodles on display and a cafe that serves 5,460 ingredients so visitors can customize their own bowls.

In Los Angeles, Jim Nakano, Glendora’s revered Donut Man, says “Japanese people don’t like herbs and spices to cover up the natural tastes of our food. Fresh foods have the best flavor.”

Yoko Isassi (yoko@ifoodstory.com) holds Japanese cooking classes in downtown Los Angeles. At her Ramen Run Down she teaches how to make tonkotsu with flavored boiled egg, tender pork chashu, umami soup stock and the most important ingredient — love. She has also held classes on the meanings behind Japanese table manners and the differences between those of China, Korea and Japan.

Masako Kawashima is a connoisseur of ramen whose favorite version is served at a nameless stand just outside the Tsukiji Fish Market but this dynamic entrepreneur proves that the sharing of foods between America and Japan is not a one-way street. After founding the sno:la yogurt company in Los Angeles, she now has Japanese outlets in Kyoto, Tokyo, Yokohama and Osaka.

By Andrea Rademan

Andrea Rademan is the former Vice President of the International Food Wine & Travel Writers Association whose articles on food travel, entertainment and lifestyle are published worldwide. She continues to follow her passion for fine dining as editor-at-large for Vegas2LA.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login